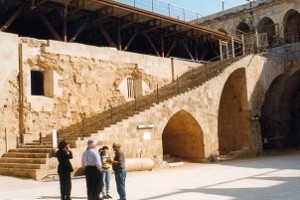

Old British prison cells hang over the lip of the recently excavated courtyard— once the main entrance to the Citadel of the great Crusader Capital.

Eliezer Stern is excited – he’s just discovered the toilets. Any traveller who has been confined to a mini-van for two hours knows the feeling. For Stern however, it’s quite different, he’s an archaeologist and these toilets are nearly one thousand years old. They were once the public latrines and there is comfortable accommodation for sixty-six with seating around the walls of a square and originally two-storied room. The discovery means that archaeologists have to sit down and rewrite their history of Akko yet again.

A Cultural Gem

Akko is often referred to as Acre and for travellers seeking a personal sense of discovery it is an amazing find. The old walled city lies north of Haifa on the eastern shores of Israel’s Mediterranean coastline a few miles south of the Syrian border. It is a cultural gem. Beneath its walls there is an entire world: the legacy of Phoenicians and Romans and the years when Richard the Lionheart recaptured the city from the Muslims after the fall of Jerusalem, built a massive and magnificent city, and made it the Crusader capital of Israel.

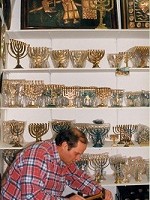

Walk the narrow streets of Akko and you will find a Jewish Synagogue, an Arab Mosque, a Christian Church, a Monastery, Convent and a Baha’i Centre. Drop into Mesika and watch Isaac the coppersmith at work on Jewish iconography or meander through the Arab Bazaar where Hamudi Kurdit will tempt you to buy from his intriguing selection of Middle Eastern spices.

Walk the narrow streets of Akko and you will find a Jewish Synagogue, an Arab Mosque, a Christian Church, a Monastery, Convent and a Baha’i Centre. Drop into Mesika and watch Isaac the coppersmith at work on Jewish iconography or meander through the Arab Bazaar where Hamudi Kurdit will tempt you to buy from his intriguing selection of Middle Eastern spices.  You can smoke an orange-flavoured tobacco nargilla (a water pipe) at Leal al Sultan, sip a Turkish coffee

You can smoke an orange-flavoured tobacco nargilla (a water pipe) at Leal al Sultan, sip a Turkish coffee  with hel next door, dine leisurely on a selection of mazetim (tapas), enjoy a succulent deep fried whole Grouper at The Pisan Harbour Galileo Restaurant, and drink local kosher wines. Christian, Jewish and Muslim families living side by side, in harmony: it is incongruous and certainly unexpected, until you know a little more of the city’s history.

with hel next door, dine leisurely on a selection of mazetim (tapas), enjoy a succulent deep fried whole Grouper at The Pisan Harbour Galileo Restaurant, and drink local kosher wines. Christian, Jewish and Muslim families living side by side, in harmony: it is incongruous and certainly unexpected, until you know a little more of the city’s history.

Akko’s Golden Age came to an end in 1291 when the great Crusader capital was captured and destroyed by the Muslims. It lay in ruins for four hundred years until Ottoman settlers built a new city which the Egyptians later transformed into an extraordinary fortification. Israel was subsequently conquered by combined British, Austrian and Turkish forces; Bahaullah, founder of the Baha’i faith, was imprisoned in Akko; and the fortress became the British jail until overrun by the Israelis and abandoned on May 4, 1947.

A Living Museum

“The history helps people understand why we have such a unique cultural mix” said David Harari, Managing Director of the Old Acre Development Company “but it also helps you appreciate the magnitude of the archaeological discoveries that are taking place and the reason for the city’s designation as a UNESCO historical site.”

The oldest city in the world is a living museum with many houses and stores occupied by families and each building supporting and supported by its neighbour while access to them is through narrow and twisting alleyways with high walls connected by thick stone arches.

The oldest city in the world is a living museum with many houses and stores occupied by families and each building supporting and supported by its neighbour while access to them is through narrow and twisting alleyways with high walls connected by thick stone arches.  It faithfully reflects the layout of Crusader Acre as it fell to the conquering Mamelukes in 1291 which is all the more ironic because the Arabs set out to completely destroy this European-Christian entity only to resurrect its original form when they rebuilt the city some 400 years later.

It faithfully reflects the layout of Crusader Acre as it fell to the conquering Mamelukes in 1291 which is all the more ironic because the Arabs set out to completely destroy this European-Christian entity only to resurrect its original form when they rebuilt the city some 400 years later.

The ongoing excavation of what is now called ‘The Underground Crusader City’ is worth the trip to Akko alone. It is an amazing feat of archaeology. Even after the fall of the city in 1291, the ruins of the Citadel, which had been the headquarters of the Knights Hospitallers of the Order of St. John, remained an impressive feature. The Ottomans built their palace on a new ground level above these ruins and filled in the Crusader halls with sand thus raising  the whole level of the northern part of the city, including the streets, and creating a clearly defined tel in which important Crusader remains are buried. Exploratory work started in 1960 and defined the location of certain halls, but the work of removing thousands of tons of sand fill and other debris had to proceed cautiously owing to the buildings and traffic above and the dubious nature of some of the foundations. Serious digging didn’t start until 1992.

the whole level of the northern part of the city, including the streets, and creating a clearly defined tel in which important Crusader remains are buried. Exploratory work started in 1960 and defined the location of certain halls, but the work of removing thousands of tons of sand fill and other debris had to proceed cautiously owing to the buildings and traffic above and the dubious nature of some of the foundations. Serious digging didn’t start until 1992.

Descending several flights of stairs you reach the Halls of the Knights: six long narrow chambers with 30 foot high vaulted ceilings and massive dividing walls connected each to the other by great arched entrances. “At first we were convinced this was the Knights’ Hall” Eliezer Stern, the archaeologist explains “but when the first chamber opened to another, and then another, we realized these were just the storeage rooms. So we had to rewrite our findings. We are still debating as to whether they contained the arsenal, emergency food rations, or grain. We know the knights didn’t store food on a regular basis because they lived on produce from the farmers— a form of taxation that made them hated wherever they went.”

Descending several flights of stairs you reach the Halls of the Knights: six long narrow chambers with 30 foot high vaulted ceilings and massive dividing walls connected each to the other by great arched entrances. “At first we were convinced this was the Knights’ Hall” Eliezer Stern, the archaeologist explains “but when the first chamber opened to another, and then another, we realized these were just the storeage rooms. So we had to rewrite our findings. We are still debating as to whether they contained the arsenal, emergency food rations, or grain. We know the knights didn’t store food on a regular basis because they lived on produce from the farmers— a form of taxation that made them hated wherever they went.”

Leaving the storeage rooms we walked out into an enormous interior courtyard.  Three of its walls showed the outlines of massive arched entranceways some of which were still bricked up and against which benches were propped, each cluttered with stone artifacts ranging from Roman capitals to cannon balls. “We found pottery and glass from Europe and China, all the trade routes. It was known in the documentation that trading was going on in the 12th and 13th century” said Stern “but until now we didn’t have the physical proof.”

Three of its walls showed the outlines of massive arched entranceways some of which were still bricked up and against which benches were propped, each cluttered with stone artifacts ranging from Roman capitals to cannon balls. “We found pottery and glass from Europe and China, all the trade routes. It was known in the documentation that trading was going on in the 12th and 13th century” said Stern “but until now we didn’t have the physical proof.”  Against the full length of the fourth wall, a wide elegant staircase rose gradually from the bottom of the courtyard to street level some thirty feet above. Stern invited me to look up at the old British prison buildings that seem to hang over the lip of the courtyard. “Did you see the film Exodus” he asked me. I nodded. “Well, if you remember the scene where the Israeli prisoners were allowed to walk around the compound each day for their exercise; they would be walking above us right now.”

Against the full length of the fourth wall, a wide elegant staircase rose gradually from the bottom of the courtyard to street level some thirty feet above. Stern invited me to look up at the old British prison buildings that seem to hang over the lip of the courtyard. “Did you see the film Exodus” he asked me. I nodded. “Well, if you remember the scene where the Israeli prisoners were allowed to walk around the compound each day for their exercise; they would be walking above us right now.”

Ongoing Underground Excavation

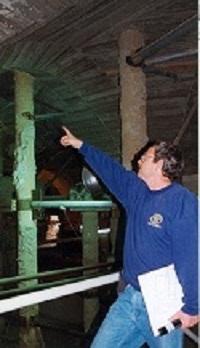

The unbelievable task of removing a depth of 12 metres of sand from such an enormous courtyard takes more than a moment to sink in, but the satisfaction in finding the staircase and walls intact must have been a reward in themselves. Exploration of the bricked archways leading off the courtyard has revealed another treasure: a magnificent cavernous room with walls that soar to an opulent ceiling.  Stern points to a small corner of the ornate ceiling. The ‘seams’ of the vaults were covered with stone ribbing fixed to the walls and resting on columns. This was the first point of entry from street level and they thought they had found the crypt of St. John. It was several years before excavation began and they were staggered when the floor continued down and the walls seemed non-existent. Once again they had to review their findings. They had found the Ceremonial Hall where England’s Richard the Lionheart and the French King, Philip August would have welcomed guests and inducted new knights.

Stern points to a small corner of the ornate ceiling. The ‘seams’ of the vaults were covered with stone ribbing fixed to the walls and resting on columns. This was the first point of entry from street level and they thought they had found the crypt of St. John. It was several years before excavation began and they were staggered when the floor continued down and the walls seemed non-existent. Once again they had to review their findings. They had found the Ceremonial Hall where England’s Richard the Lionheart and the French King, Philip August would have welcomed guests and inducted new knights.

We return to the courtyard and Stern takes me over to the well. When they discovered it, they expected that this could lead them to the main water supply and by draining it down were able to trace small shafts that led to the main conduit for fresh water. Ultimately this led them to the underground system that served the city and they hoped that within three years they would find the public latrines that needed water to flush out the sewage. They found them in three months

Each tier of stone seats is connected by a horizontal and presumably inclining shaft to a vertical duct that drops down into an arched stone corridor and the conduit for sewage. As they dig down into the collective sewage room and out to the main drains, they wonder whether they will connect with an ‘escape route’. If so the question arose as to whether the underground corridor is really the sewage system for the city and whether their search for the escape route will have to begin all over again.

Each tier of stone seats is connected by a horizontal and presumably inclining shaft to a vertical duct that drops down into an arched stone corridor and the conduit for sewage. As they dig down into the collective sewage room and out to the main drains, they wonder whether they will connect with an ‘escape route’. If so the question arose as to whether the underground corridor is really the sewage system for the city and whether their search for the escape route will have to begin all over again.

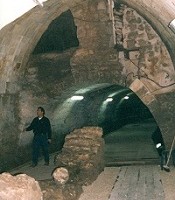

Secret Passages

Every Templar City had secret passages and vented underground corridors so that the occupants could escape if capture was imminent.  Akko was no exception and some years ago they found an escape route that crosses underneath the city. Once again they were faced with cutting their way through thick debris which had hardened over time. The tunnel leads eastward from the fortress, the remains of which are now covered by the sea. The lower part of the tunnel was carved from natural stone, and its upper part was built from hewn stones covered by a semi-barreled dome. The tunnel traverses the Pisan Quarter and leads to the city port in the east, a distance of 350 meters. A boardwalk has been created along the length of the tunnel with channels either side for the rainwater. It is now open to the public.

Akko was no exception and some years ago they found an escape route that crosses underneath the city. Once again they were faced with cutting their way through thick debris which had hardened over time. The tunnel leads eastward from the fortress, the remains of which are now covered by the sea. The lower part of the tunnel was carved from natural stone, and its upper part was built from hewn stones covered by a semi-barreled dome. The tunnel traverses the Pisan Quarter and leads to the city port in the east, a distance of 350 meters. A boardwalk has been created along the length of the tunnel with channels either side for the rainwater. It is now open to the public.

But stunning as that underground corridor is, and with its height and breadth, you can easily visualize the Knights moving quickly and orderly through its length; it was the sewage system that I found most fascinating and that has proven to be a key to all the buildings still buried in Old Akko. This narrow underground stone corridor travels under the City. Rainwater from the streets and water from the houses above would have poured down through small channels in the ceiling and then flowed out along its length to the sea. These channels are the keys to the Old City and helping archaeologists map the buildings that still exist buried under modern Akko. Revelations that continue to make this ancient city one of the most exciting tourism finds  for many years to come.

for many years to come.

Travel Notes: Accommodation in Old Akko is limited but new hotels are being built. At the time I visited, there was a Hostel (972/04-991-1982) that offered a bed in the dormitory or a private room, and the Palm Beach, a resort hotel (972/04-981-5815) just south of Akko. For more information: www.akko.org.il