Have you ever promised yourself a vacation, but work kept getting in the way? That’s been the story for years for Heather M, a friend and colleague. Oh, she’d managed the odd weekend getaway, but what she wanted was Europe, Adventure, the Grand Tour, the Great Escape. Well, this summer the office is closed, the ‘phone is off, and she’s on her way. Follow Heather’s adventures in the Destinations category of this website.

Have you ever promised yourself a vacation, but work kept getting in the way? That’s been the story for years for Heather M, a friend and colleague. Oh, she’d managed the odd weekend getaway, but what she wanted was Europe, Adventure, the Grand Tour, the Great Escape. Well, this summer the office is closed, the ‘phone is off, and she’s on her way. Follow Heather’s adventures in the Destinations category of this website.

(Image: The Church of St. Lorenzo, a distinctive landmark in the village of Soglio, Val Bregaglia, Switzerland. Copyright: Switzerland Tourism. By-line: Swiss-image.ch/Andreas Gerth. Image licenced for this website only, additional licence needed to forward or copy.)

July 30: To Toronto on Air Canada. A seating mix-up irritates the attendants who fall to blaming the gate personnel. Not helpful and not pleasant. Good reason to switch airlines.

July 29: Train to Paris to the Hotel de Marronniers, buried in a courtyard, far from the street, very quiet. I settle into the walled garden with a book. Early to bed to be ready for the 7:15 a.m. airport shuttle tomorrow.

July 28: We visit Sarlat, a beautiful village hundreds of years old. A town fought over by many, fortified, conquered, and reconquered. The architecture is arresting if you look up. At ground levels it’s modern shops and restaurants. It feels like a mall, not a medieval village.

We’re on our way back to the farm, where we find the electricity interrupted, meaning no power to the fence keeping the donkeys home. The donkeys do not understand electricity. They are still in the field, only dreaming of wandering.

July 27: Sunflowers everywhere.

Photo Credit: Helga Haberfellner

Fields and fields of yellow, grown for seeds for oil. Passing a small town, on the way to Monflanquin we see it dressed for a festival. It’s Beaumont, not in the guide book. We ask at the tourist office, who are the decorations for? For you, they reply, for tourists. Welcome. A wine merchant sells from a tiny table in the market square. Softened by the welcome, we buy several bottles. There’s an ankle-level water tap for dogs. It’s 32 degrees. The dogs would say thank you if they could.

July 26: Bordeaux region is known for wine,

Photo Credit: Helga Haberfellner

so we go to St. Emilion, the centre of world-famous vineyards. The Relais et Chateaux hotel offers breakfast: Poached egg: 48 Euros ($67.20). I’m willing to pay to find out what they do to a simple hen’s egg for that price. My companions pull me away from the restaurant door. The town is lined with wine shops. It’s a wealthy town, judging by the parking lot. We see an Aston Martin and a Mercedes Maybach.

July 25: This is Eleanor of Aquitaine country.

Photo Credit: Helga Haberfellner

We want to visit the church she built in Talmont, partly for herself, the spousal plaything of kings lusting for her extensive property, and partly for pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago. The village is small whitewashed houses and steroid-fueled hollyhocks, eight and nine feet tall.

July 24: Leaving the farm for Bordeaux with my hosts and their two dogs, the Porcelaine, and a Labrador cross. The plan was to stay in bed and breakfasts. Many say dogs are welcome, but they are fibbing. They mean small dogs. Or one dog at a time. After hours of frustration, my hosts find the only welcome near Bordeaux. It’s a farm about two kilometers from Issigeac. They raise pigs and breed cocker spaniels. The directions tell us what not to do: Do not take this road, do not take that bypass, do not stop at the veterinarian, do not close the open gate, do not open the closed gate, and, above all, do not enter the courtyard. Honk instead. We feel intimidated. The drive is littered with rusted farm machinery. The dogs are hot and hungry. A horse tied to a tree. A 16-year-old boy, wearing only grey short shots answers our honk, opens the closed gate and says, “Unh?” We explain. He says nothing. He points us to our rooms and disappears. There’s a backyard size field, which we see, by the excrement, is the horse’s usual haunt. A grey cat stretches voluptuously in the best chair. The dogs are intrigued but the cat has claws. We move the cat; feed the dogs, and ourselves. Suddenly appears four riotous cocker-spaniel puppies, two-months-old coal-black, not entirely able to climb the stairs, but straining to try. They possess our hearts. Our dogs start to make friends, but the puppies are too bouncy for their stately approach. Ours back off, sigh, and nap.

Mme Bolze, proprietor, arrives, just as we are climbing into the car to explore the village. She waves away the car: The village is just down the road, yes? There is daylight until 10 p.m., no? The car is not necessary, yes? You can walk, understand well? So we walk the farm road, rutted, pitted, troughed by runoff, two kilometers to Issigeac. The dogs are nose-down happy, with hundreds of new scents. We go to the only place open, a bar. We ask for the dessert menu. Astonishingly, there is one. We order profiteroles and the local rosé. We walk out to a patio full of locals. They discuss when M. Untel pretended to be a lawyer. That leads to what to drink to get drunk the fastest. They accept the dogs with a glance, but we humans are objects of curiosity.

July 23: Happily at work in my hosts’ garden,

Photo Credit: Helga Haberfellner

trimming roses, cutting back grape vines and learning new plants. White lavender is new to me. The hedges are rosemary. The growing season is February to November. I feel jealousy. A neighbour, René visits with fruit from his orchard. And a bottle, of course. This is France.

July 22: Other friends arrive. We go to Turenne and Colognes la Rouge two of the “most beautiful villages in France.”

Photo Credit: Helga Haberfellner

The first is a hill town with a castle on top. All the buildings are stone, built to harmonize with each other. A steep climb reveals wonderful views of the countryside. An art exhibition is advertised at the foot of the hill. At the top, it’s not open until 2 p.m. Colognes la Rouge is more tourist-y, good at self promotion. Its medieval houses are all red brick, using the iron-rich local soil. A comfortable walk through the village shows the different styles of building and their period embellishments. Only the church is open to the public.

We are invited to our hosts’ aunt’s house for lunch. She lives in a classic farmhouse with steeply pitched roof and four blue-painted French doors. There’s a swimming pool, welcome in today’s 30 degree heat. Lunch begins at 3 p.m. and ends at 6 p.m. The aunt’s hobby is showing cocker spaniels. Trophies line two shelves, a tribute to her good eye. She prepares for the Brive dog show on August 11.

Photo Credit: Helga Haberfellner

She will show her dog, and, in the rare breed category, my hosts’ Porcelaine. Much later I check the results: The Porcelaine wins the Porcelaine category because she is so rare she is the only entry. And, at 15 years old, she wins the veterans’ category, the nearest rival being a spry eight.

July 19: I watch grass grow. I’m at a farm in Feraud, a hamlet of 10 houses, two abandoned.

Photo Credit: Helga Haberfellner

Toronto friends bought the farm as their summer retreat. It’s peaceful, with a beautiful view of rolling hills and leafy trees. Three donkeys munch grass. There is nothing to do. I do nothing.

July 18: Goodbye to Amanda who goes by Eurostar to London. My train to Limoges actually goes to Limoges, after days of doubt and outlandish alternative routes consequent on a track blocked by a derailment five days earlier.

July 17: To the cathedral Notre Dame, dating from the 10th century, on an island in the Seine. We were lucky to happen on two choirs singing hymns in marvelous acoustics. Nobody said the names of the choirs, or where they were from. We looked in the chapels, but did not go up the bell tower. A mass started at noon. Signs said the nave is now reserved for Roman Catholic worshippers. We leave to walk the rest of the island and the companion island, Ile St. Louis. It felt very country, right in the middle of Paris, which may be why apartments there are so coveted. Amanda went to the Louvre, where she photographed tourists eight deep before the Mona Lisa, holding up phone cameras to record themselves with the painting. I went to the Guimet museum of Asian art. It displays mostly sculpture in stone, from Thailand, Cambodia and India. The temporary exhibition of Japanese textiles, dyed using the resist method, was my favourite with its images of huge carp, cranes, and other symbols of luck, prosperity and longevity. This is our last night in Paris. We must pack, and put the apartment in order. We buy foodstuffs from excellent stores about 50 meters away, a bottle of wine, and get busy.

July 16: Today we devote to eating well. We asked three Toronto foodies for restaurant recommendations. All three recommended Chez l’ami Jean, a small restaurant near the Eiffel Tower. We chose lunch because we couldn’t get a dinner reservation. Pretending we were French, we first ordered wine. Then we were served a bowl of crisped pork-belly bits and green peas, with a jug of whipped mushroom soup to pour on top. Sighs of contentment. We could see Chef Jean in the kitchen paying careful attention to every dish he sent forth. Next we had perfectly cooked fish in white wine sauce with pureed potatoes. Then an offer of dessert, which we postpone. We leaned back, stuck out our legs, discussed the world, and digested. We revived for dessert. The house specialty is sophisticated rice pudding, like nothing I ever had as a child. More like a sweet rice risotto, made with whipping cream. There is thick caramel and a custardy sauce to spoon on top. We were the last patrons, all others returned to work. The waiter offered an extra dessert “ile flottant” or floating island to anybody with a U.K. background. Again a children’s dessert raised to sophistication. And then a thanks-for-coming present: a box of almond meringue cookies and chocolate coated almonds. We abandoned our afternoon agenda. We taxied home to lie down and digest. In the evening, off to the Palais Royale where an offshoot of the Comedie Francaise hosted a theatre festival. We saw a South Korean production, Symphoca de Princesse Bari, a mix of dance, mime, costume drama, and acrobatics. I could not quite follow the story which seemed to be about a princess forced to marry against her will who then uses wiles to save her dying father. Home to a tiny crust of cheese, and a wish that Chez l’ami Jean were in Toronto.

July 15: The Jacquemart-Andre museum. M. Andre, a wealthy bachelor in his 40s, having built a great mansion on the Blvd. Haussmann, looked about for a wife. He found Mlle. Jacquemart, a young artist. They married and set out to vacuum up as many art works as they could. The art works, sculpture, painting, ceramics, are all still in the mansion, along with the owners’ opulent furniture. There is so much it’s bewildering. As the brochure sniffs, Mlle. Jaquemart was a decorator, not a curator. We notice two mesmerizing Rembrandts displayed in no special way.

Then to the Pompidou Centre, said to have the finest collection of modern art in Europe. I wish I had more time there. It has a rooftop bar, overlooking Paris, Notre Dame, towers, spires; a wonderful view. Next: a concert at the Sainte-Chapelle entry by way of the Palais de Justice. The church is mostly stained glass windows in brilliant colours telling Bible stories to a public that could not read, it being the 12th century. The concert began badly with the quartet playing Pachebel’s Cannon out of time with each other. We could see, but not hear, the musicians’ remarks to one another at the end of the piece. It must have been a call to discipline because they then played Vivaldi’s Four Seasons in harmony.

July 14: Police divers look for a bomb in the Canal St. Martin. The road is blocked. The bomb disposal truck stands by. It’s July 14, Bastille Day, a national holiday celebrated with military parades and fireworks. Not bombs. The divers surface with nothing. The crowd cheers. A hoax, after all. The Canal St Martin is a working canal almost in the heart of the city. Walking the quay side is a quiet leafy break from urban bustle elsewhere. The canal was in a forgotten quarter, containing light industry and artists in search of cheap rents, until a French president said he wanted an auto route. After all, the canal was a die-straight thoroughfare. There was just the little problem of water in the canal. Engineers could solve that. Uproar! Canal stayed serene, but the quarter was discovered. It is gentrifying. Artists cannot now afford the rents. Only the little park remains the same. It’s the sleeping place for Afghan refugees, while the government debates how to accommodate them. Being from Toronto, we naturally check real estate prices. The cheapest we find is 100,000 Euros ($140,000) for a 12 square meter room (nine by 13 feet), with a tap, and, as the “possibility of WC.” The ad does not say what to do until the toilet is installed. The best is 2,900,000 Euros ($4,060,000) for a two-bedroom apartment on the Ile St. Louis with eight windows overlooking the Seine. We visit Père Lachaise Cemetery burial place of the famous. Some graves, for example Jim Morrison’s, have extra security against vandalism. The guide is amusing. The location creepy. Dinner at our Paris friend’s apartment, with her husband and 28-year-old son, who tells us Canada should better treat its indigenous population.

July 13: We must up our game if we are to see everything on our list. To the d’Orsay for more Impressionists. Three floors are closed, a big disappointment. It is crowded, unlike the Marmottan. After fuelling up with a salmon lunch, we taxi to the Rodin museum and garden. Rodin first rented studio space here, on the recommendation of tenant Rainer Marie Rilke, and then took over the whole building in 1911. The Gates of Hell are here, the sculpture project which nearly did for Rodin, says his biography, because it was so difficult to execute. Other famous pieces here: The Kiss, The Thinker, The Burghers of Calais. The garden is formal, in the French style, except the topiary trees sigh, laugh, and groan, startling everybody. Erik Samakh designed the soundscape. It is meant to surprise. We shop for supper in the French manner; letting the greengrocer feel which peaches will be ripe in two hours when we will eat them. The butcher has stuffed veal breast on offer, as well as 12 kinds of pâté. The wine clerk agreeably tells us about bottles from vineyards too small to export to the LCBO. The pastry shop sells only one kind of cookie but in dozens of flavours. All these shops are within 50 meters of our apartment.

July 12: Off to see the Monets at the museum Marmottan. This is an elegant house, left to the state by its owner, with a collection of Impressionists and second empire furniture. A special exhibition of Marie Laurencin paintings was a surprise addition. The Metro to Bastille. A walk through the Place des Vosges and its many art galleries and shops. How to ship home the life-size sculpture of a sumo wrestler, in red fiberglass, crouched to spring? We did not know how, so we did not buy. I imagined a quiet ‘Thank God’ from our partners at home. To the theatre for an evening dance performance by Droles des Mecs. More gymnasts than dancers, and lots of fun to watch.

July 11: Train to Geneva and train to Paris. A Paris friend met the train – so welcoming a friendly face on the platform! We rented an apartment in the Marais. Our Paris friend showed us how La Fourchette.com worked. It’s a website with last-minute deep discounts at restaurants, 40 percent at the restaurant we chose. An exceptional meal: Lamb slowly roasted for seven hours, rare tuna steaks, salads with savoury dressing, a local wine recommended by management. Even our Paris friend, no stranger to good eating, said the restaurant was a find.

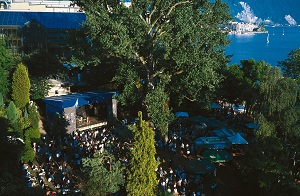

July 10: Nobody gets up early at a music festival so we wander onto the ferry to the small towns at our end of Lake Geneva.

Photo Credit: Swiss Tourism

Between Montreux and Vevey are chateau-like second homes for the wealthy. Alas, none asked us to dinner. Municipalities now have a ceiling of 20 per cent second homes, to avoid emptying the town in the off-season as happens in rural France. We saw news articles reassuring people the second-home market remained strong, all quoting real estate agencies as sources. Tonight’s concert: Misja Fitzgerald Michel on guitar, Olivier Koumdouno on cello and Hugh Coltman on vocals. Exceptional! I will look for their recordings. And that was just the opening act. The headliner was Avishai Cohen, who played three encores, and could have held the crowd for five or six more.

July 9 (later): A surprise at the Montreux Jazz Festival.

Photo Credit: Swiss Tourism

The opening act is from Toronto. A trio, Bad Bad Not Good, electro jazz. Skilled musicians in their 20s. First time at Montreux. Headline act is Charles Bradley, for whom fame started in his sixties. Why? He imitates James Brown (badly) and attempts to dance like Michael Jackson (worse). He shouts, he does not sing. He calls himself the love machine, falls on his knees, microphone between his thighs, thrusts his pelvis as if he had a five-foot erection. Ewwww. We wish he would get off the stage so his really excellent band could play. Bradley never introduces his band members. Perhaps he knew they were better musicians than he, and did not want any acknowledgment to go their way. The Royal Plaza is a wonderful hotel, more wonderful because it upgraded us: this because it can’t sell the rooms overlooking the outdoor jazz concerts. It’s noisy. Except to us. We are here for the noise.

July 9: Herders drive goats down the street (Zermatt is car-free, giving goats their chance).

Photo Credit: Swiss Tourism

Five men in mountain costume step into the street to play long alpine horns. It’s time for the train to the Montreux Jazz Festival. The first thing we see is the Festival poster: “If it’s too loud, you’re too old.” The next is the government’s poster. It says concerts may exceed 100 decibels. Hearing may be impaired. Protect yourself. Take ear plugs from the bin below. Who is the bureaucrat who decided ear plugs are better public health protection than condoms at an all-night music festival?

July 8: From St. Moritz to Zermatt on the train with huge windows

Photo Credit: Swiss Tourism

to see the mountains and waterfalls and gorges and viaducts and cows and big-horned sheep. Zermatt is entirely a resort town. All alpine style buildings even the seven-storey ones. Glamorous shops with famous brand names. If you want to test the politeness of salespeople, take your $9.98 watch to a boutique selling $26,000 watches. I ask for a new battery. “Our watchmaker will be in Friday,” she said.

“Why do we need the watchmaker?” I asked. “To take off the back without hurting the works.” I pop the back with my thumbnail. A little frown appears. A jeweler’s loupe comes out. The atmosphere frosts. “We cannot help you, Madame.” Exit, as Shakespeare says, pursued by a bear.

Zermatt has the Matterhorn which one can ski, or climb after long training. Or one can take a cable car to 3,380 meters. Instead we head for a restaurant recommended by a gourmet guide, Le Crevin. We eat perfectly cooked salmon and listen to two sixty year old American men brag about how important they were in college, while their wives traded strategies for coping with their husbands’ health problems.

July 7: St. Moritz is closed tight because it’s Sunday. Still, a pleasure to see a genuine Prada store instead of furtive men on Venice bridges selling knock-offs. This is a rest day but not an idle day. We go to a morning classical music concert where the trio unexpectedly plays Elgar. It wasn’t on the program. The pianist suddenly got up, dug sheet music out of a cupboard, and passed it to the cellist and violinist.

Photo Credit: Swiss Tourism

We take gondolas to mountain tops, look about like rulers of the world, then walk down through colourful fields of wildflowers. By then restaurant kitchens are closed for the afternoon. What to do? We are hungry. We head to the five-star Hotel Kulm which comforts us with barley soup. In return we promise to come back for the 5 p.m. opera.

At 4:30 we ask for last-minute tickets. The languages here are German and Italian. Our English “last-minute” is understood as “discount.” We’re told to wait in case it’s not sold out. We take positions on either side of the staircase, obvious foreigners in our jeans jackets and mountain-dusty shoes. Everybody else is dressed up. Many men wear collarless boiled wool jackets with silver buttons, and two women wear blonde braids circling their heads. Finally we are offered 190 franc tickets for 100 francs. We grab them. It’s Don Giovanni, sung in Italian. The set designer was challenged because the ballroom is a long rectangle with seating at both narrow ends. A 35-piece orchestra needs seats in the middle of one long side. Where could the singers be? The designer built two-storey moveable shelves on each long side, and a catwalk in front of the orchestra. The costumes were period, until Don Giovanni revealed, above his satin trousers, “Tommy Hilfinger” on the waistband of his underpants. At intermission I introduce myself to a performer I hear speaking English. He said he spent five years in Toronto. “Did you sing with the Canadian Opera Company?” I ask. “Oh, no,” he said. “I worked for a Swiss reinsurance company.” Later, at a nearby restaurant, applause starts when the Don Giovanni walks in wearing jeans and a T-shirt, no underwear visible. He sits next to the prettiest blonde. She is pink with pleasure. Clearly there will be another act this evening.

July 6: Out the door grumbling at 6 a.m. to get the 7:10 train to Lugano, Switzerland. At the frontier, the guard asks four East Indians for their passports but not us. Embarrassed, we wave ours anyway. At Lugano we board a bus and head straight back to Italy. That is the fastest route to Tirano, Switzerland. There are mountains in the way. At last we are ready to start the journey we came to Switzerland for: The mountain-pass trains. The Bernina Express to St. Moritz and the Glacier Express to Zermatt.

Constructing the railway so high in the mountains, bridging streams and blasting tunnels

Photo Credit: Swiss Tourism

is a wonder to engineers. We look up, through glass which domes the train ceiling. The mountains are green to the tree line, then grey to the sky. Waterfalls everywhere bring snowmelt to pastures with cows, sheep and goats. And yes, the cows really do wear those bells seen in tourist ads. We arrive in St. Moritz, a wealthy ski and health resort, where a large Rolls Royce, from the five-star Palace Hotel, waits for our train companions. We’ve been curious about this six-person family whom we heard planning a bar mitzvah while ordering ham sandwiches. They are thrilled with the Rolls Royce, and its uniformed driver, with pillbox hat. They take pictures of each other with the car, then with the driver. We climb into the modest van of the three-star Hotel Eden. Our balcony faces a mountain range and overlooks the lake. We must celebrate this soothing green-blue view so we look for a wine store. We find a bar, where neither French nor English is spoken. We order with hand gestures. We have no corkscrew. We mime opening the bottle, gestures learned long ago at the Mary Beatle Ballet School. Fed up with our comedy, the proprietor gives us a corkscrew and escorts us to the door.

July 5: The day to separate and regroup. Georgina goes to Sienna for a writing seminar. I go to Milan to meet Amanda, who will be in a black mood after the indifferent invasiveness of the Heathrow guards. We’ve scored tickets to see Da Vinci’s Last Supper, frescoed on the wall of a Milanese abbey. The tickets are for 15 minutes only, with a group of 25, at the precise time of 3:15. This is northern Italy. They mean it. Be late, be left at the door. This is the Last Supper the moment after Jesus says he knows one of the disciples will betray him. They look at each other in surprise, denial, indignation, wanting to know, who? Only Judas looks directly at Jesus, holding silver pieces in his right hand. We are ushered out smartly. We walk to the castle museum displaying artifacts from pre-Roman times to the present. A highlight is an unfinished Pieta by Michelangelo with two figures but five arms.

July 4: More art! We are loyal, so we jump on the Vaporetto to visit two Newfoundland artists exhibiting in a fabulous Grand Canal palace. The artists are not there; too bad; we hoped for an accent from home. On to the Irish Exhibition. It is a multi-screen film from the eastern Congo where 4.5 million people were killed in decades-long fighting. Everything green in nature is red in the film, a metaphor for bloodshed. We heard great reviews for the Iraq Exhibition, also in a Grand Canal Palace. It showcases five artists actually working in Iraq. Overcoming the war’s destruction is the theme. A satiric cartoonist pokes fun at authorities; the furniture in one room is entirely hand-made of cardboard: bed, tables, chairs, wardrobe, wall-calendar. A film documents youths smuggling alcohol into Iran, where it is strictly forbidden. The smugglers say it is the only work they can get. There are landmines to avoid and guards to bribe. Otherwise, the guards may shoot the smugglers and their horses, leaving the guards a windfall of booze at the border. Back to the Vaporetto and on to the nearest island, San Giorgio Maggiore for Marc Quinn’s indoor and outdoor sculptures, including an 11 meter high inflatable woman without arms. The church hosts John Pawson’s experiment with a crystal lens in an upside-down dome under the church’s right side up dome. We ride the elevator to the bell tower with the best view of Venice. We find a professional photographer with two cameras on tripods aimed at the harbour exit. “What are you waiting for?” I ask. “A ship to leave,” he says. His assistant is talking excitedly on her cell. She reports the ship waits for two passengers lost in Venice. But cruise ships never wait. If you miss departure, you must find your own way to the next port. This ship cannot leave because the lost passengers’ children are in the daycare – way too many legal problems making off with other people’s children. The ship eventually towers on the skyline. It’s the Disney Magic; huge; dwarfing everything. The Venetians are reluctant hosts to enormous cruise ships; but they have no choice. The harbour belongs to Italy, not Venice. Italy collects lots of harbor fees.

Last night in Venice. We try for a good dinner, following restaurant recommendations in a Venetian cookbook. First place waiter says it is not a restaurant, but it will serve “meat plate, fish plate, or ham and cheese plate” for 44 Euros each ($61.60). We ask, what is on the plate? What about vegetables? “Meat plate, fish plate or ham and cheese plate, 44 Euros” is the answer. We move on. To the end of a dark alley to a door displaying a mouth-watering menu. We can’t open the door. We back up. Read the opening hours again. This is an open hour, but the door is locked. We settle for the local pizza joint. We agree to return for the 2015 Biennale.

July 3: Back to the Biennale, this time to the Arsenale location. Many exhibitions are installations, some include soundscapes.

Photo Credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

There are conventional paintings — especially interesting when it’s from an artist about which one knows nothing; for example, Papa Ibra Tall, exhibiting from Senegal.

July 2: To the art fair, the Biennale, the reason we are in Venice. Many countries, including Canada, have permanent pavilions in the

Georgina in the café at the Biennale

gardens where the exhibition occurs every odd-numbered year. Other countries exhibit in the Arsenale, huge industrial buildings where ships used to be built.

Shary Boyle is the Canadian artists chosen this year. Just on the edge of kitsch, it’s a fascinating installation but too dark to take photos.

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

Jeremy Deller is the British choice. He painted two walls with social commentary. One is a hen harrier crushing a Landrover in a talon. That references the death of two hen harriers (a highly endangered species) by shotguns fired from Queen Elizabeth’s Sandringham estate at a time when only Prince Harry and a friend were hunting. The bodies were never found, so no consequences befell the shooters.

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

The other references the Biennale of 2011 when Russian oligarch Abramovitch docked his 377 foot yacht near the Biennale and blocked access with his security entourage. For that, Deller brought social reformer William Morris back to life to hurl the yacht into the sea.

June 30: To Venice by train with a winning soccer team of 15-year-olds their silver trophy and gold medals round their necks. Steps from the train station lead directly to the water, lest one forget that Venice’s roads are canals. Boats are the public transport. There are no cars at all. We find the correct boat going in the correct direction and start down the Grand Canal. Venice is often called the most beautiful city in the world. It’s easy to see why as the beautiful facades of graceful houses and palaces slide by.

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

We share the canal with gondolas, long narrow black boats with high prows and gondoliers in striped shirts and straw hats standing at the back steering with one oar. Then there are private boats, water taxi boats, and service boats including a nap-inducing laundry boat.

We later see, from the terrace of the Danielli hotel, even more canal chaos with 10-storey cruise ships being steered out to sea by tugs, the hydrofoil going to Croatia and the mega-yachts of mega-rich visitors. Everybody goes in different directions and somehow nobody collides.

Venice has 400 bridges over canals and we cross six of them to get to our rented apartment in a residential district, just like a village inside a village: There’s a cheese store, a vegetable store, a wine store, a bakery, a newsstand, all within 100 meters.

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

To the Peggy Guggenheim museum. It’s the house where she lived for 30 years, supporting artists, collecting their work, and inviting them to stay. A perfect example of Venice’s romantic grip. Peggy Guggenheim could have lived anywhere, and she chose and stayed in Venice. The result is a magnificent collection of contemporary painting and sculpture.

Then for something completely different, we went to the Lido, a separate island with a wide sand beach and roads with cars and buses and huge holiday hotels. We walk along the beach admiring the serious sunbathers. We are the only ones wearing hats. Or shirts.

June 29: to Italy; to Trieste in time for lunch at Trattoria Menarosti, another perfect fresh fish, and strudel we saw coming out of the oven. A restaurant find for sure.

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

On to the main square and Café degli Specchi, dating from the 1830s, and this afternoon, home to operetta. A sell-out at five Euro, including two half-inch square sandwiches on skewers before and risotto after.

June 28: We stayed in Louvran, one of the prettiest towns, then drove over pine forest mountains to Pula, with its Roman arena, smaller than the Rome coliseum, but far less crowded. Pula repaired and rebuilt after bomb damage in World War II. UNESCO denied it World Heritage status because of the rebuilding.

How to eat fresh-grilled sardines: Pick up by the tail, peel flesh from each side, return the perfect skeleton to the plate. Repeat. With grilled vegetables, sitting by the sea in a trailer park, a delicious lunch. “My brother owns this restaurant,” remarked our guide, in answer to our unspoken question, “Why are we in a trailer park?”

At lunch Georgina and Beppo, the guide, talked about languages with declensions, reciting those they knew. “You forgot the ablative,” yelled a waiter, clearly underemployed at the trailer park

June 27: Last day in Split with its beautiful sea front. Lunch at the No Stress café on the ancient main square. A chef-run café. Best meal so far. Rare steak, very fresh salad. On to the Istrian peninsula, a popular vacation destination because of its long coast line, beaches, clear water and dense pine forests. The air smells wonderful with hundreds of oleanders in bloom, pink, white and red.

June 26, 2013

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

Today is time-out. No art. No architecture. Nature. We go to Krka national park, take a boat to a vast waterfall. We must leave the boat and climb to the top, there being no lift lock. There we take another boat to Roski slap, slap being the Croatian word for waterfall. A peaceful day on the water. Blue sky, white clouds, green trees, green water, and the occasional white swan. Very restful.

June 25, 2013

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

Split. A National holiday, statehood day. Museums closed. Diocletian Palace open. The outer walls still exist; the interior buildings were destroyed long ago and replaced by local housing. Twenty years ago, said the guide, it was all prostitutes, addicts and homeless. Now there’s a changing of the guard (centurions, Diocletian and Mrs. Diocletian appearing on a balcony). Only the cellars, some pillars and sphinxes looted from Greece and Egypt remain from Diocletian’s time.

Diocletian sited the palace over sulphur springs because he had rheumatism. Now the fish market takes advantage of sulphur repelling flies. How do those fish sellers get their gravel- in- the- amplifier voices? I missed those classes.

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

There are only 100 Jews in Split. We go to the synagogue to pay our respects. It’s staffed by volunteers, but none are there today. We go to the Jewish cemetery, 105 stone steps above the city. It was, opened in 1570. The mortuary is now a café called Burn. The café keeps the key to the cemetery gate. The grave markers are partly destroyed, partly covered in debris. We leave stones to record our visit. We wonder what to do to find help to preserve this 500-year-old certitude of faith.

June 24, 2013

How does a fish get to be the runner up in a contest it didn’t enter and would avoid if it could? Tonight’s menu in Split offers “second class fish 340 kn/kg” or “first class fish” 380 kn/kg.

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

How did we become invisible in Bosnia? Croatia’s border patrol checked us out of Croatia and eight kilometers later, welcomed us back. We’d been in Bosnia for ten minutes. Where were the Bosnian border guards? “They are resting,” said our driver.

Today we explored Ston, another walled medieval city; this time a real city with real people living there, doing their laundry, growing figs and gossiping cheerfully. Ston’s wall, 5.5 km, is second in length to the Great Wall of China. It stopped salt thieves in the 15th century when salt cost as much as silver. Ston still produces salt, but nobody trades silver for it.

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

Off to the island of Korcula another walled town is laid out like a fish skeleton. All streets facing west are straight to encourage the ocean breeze to air the town. All facing east are curved so the cold east wind is prevented. Lunch at Nonni, where they hand roll pasta on sticks to get macaroni. Lots of garlic. Also a present of fig and almond dumplings. Very good indeed.

Spectacular drive from Korcula to Split through hills and valleys and switchbacks and hairpins. Lush fertile valleys below, growing vegetables and fruit. The hills end steeply in the sea and rivers. There’s a scant foreshore but on what there is people spread towels, sun bake, and step into the sea (temperature 24 C).

June 23, 2013

To Montenegro, which separated from Serbia in 2006 to find some essentials of independence, such as its own currency, irksome. It uses the Euro instead.

We stop at Perast for a 300-year story of faith. In 1452 fisherman found an icon of the Madonna and child on a rock facing their tiny village. Clearly a church must be built on that two meter square rock. For two hundred years the citizens dumped seized ships and rubble to make the island. Then they asked the talented 14-year-old Tiepolo to paint a religious image. His painting is in the attached museum. Wikipedia says that’s nonsense. The painter was Tripo Kokolja. The altar piece is the painting found so long ago. When photographed, it mysteriously shows the ghosts of fishermen past.

We stop at Perast for a 300-year story of faith. In 1452 fisherman found an icon of the Madonna and child on a rock facing their tiny village. Clearly a church must be built on that two meter square rock. For two hundred years the citizens dumped seized ships and rubble to make the island. Then they asked the talented 14-year-old Tiepolo to paint a religious image. His painting is in the attached museum. Wikipedia says that’s nonsense. The painter was Tripo Kokolja. The altar piece is the painting found so long ago. When photographed, it mysteriously shows the ghosts of fishermen past.

On to Kotor, a walled town with a church named Our Lady of Health. That’s what is needed to climb the switchbacks to get there.

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

June 22, 2013

Swimming in Dubrovnik is about access to the sea. There’s the Bellevue Hotel with its elevator down the cliff, but only for Bellevue guests. And then there’s Buȥa where a $4.00 bottle of water opens stairs to the sea. That’s where I am, feeling smug for finding it hidden behind the city wall, through an iron gate and down a narrow passage. Outside the railing, swimming is free. If you take a four-steamboat – jump off the cliff.

I’m watching an eight-deck Costa cruise ship leave. It’s finished adding its passengers to the 12,000 who daily flood the 800 Old Town residents. Tourism is the only business in Dubrovnik. It’s becoming a museum city, like Venice and Florence. Half the Old Town buildings were bought by foreigners, carpet-bagging after the 1990’s war. The money bought food and shelter for devastated residents without work. Now the government controls purchases to prevent the Old Town becoming the Ghost Town for the 11 months the foreigners are not at these second homes.

There’s a hang glider in the sky, sea kayakers paddling to a close island and French tourists playing pick-up water polo directly below.

Photo credit: Georgina Steinsky-Schwartz

The Old Town is a limestone walled city started in the 13th century. The roads, the stairs and the buildings are the same limestone, giving remarkable uniformity to the town. The Old Town is a rare flat place among mountains and a UNESCO World Heritage site. Our apartment, 110 stairs above the Old Town is built into the wall. That’s how we found Buȥa. We watched people disappearing into the wall, with only the sea on the other side. Like ants in the kitchen, I had to find out where they were going.

The Old Town Italianate Gothic buildings were a surprise until I learned that after the 1700 something earthquake the Italians moved in to reconstruct. After the 1990’s war, reconstruction was local. Now half the Cabinet of the 1990’s is in jail for corruption.

Everybody talks about the 1990’s war. I asked the driver if the years of peace made Croatians friends with the Serbs and the Bosnians and the Montenegrians. “Never,” he said. “We forgive, but we do not forget.”

June 21 2013

You gotta love Lufthansa. I’m on time from Canada to meet G for the Vienna – Dubrovnik flight. G. coming from Prague is going to miss the flight. Lufthansa snaps into “Not our passenger” mode. It sends a bus onto the tarmac, orders stairs, quick-marches through customs and immigration, orders the Dubrovnik flight to wait, send the bus back onto the tarmac and delivers G to the door. Total delay to the Dubrovnik flight? Five minutes. Arrive Dubrovnik. George, the driver sent by the travel agency, takes us to the five-star Bellevue Hotel, leaves. No reservation. The hotel phones the agency. George returns and says, “I’m not perfect,” and delivers us to the Old Town, were we are supposed to be. The Bellevue staff were exquisitely polite. Noblesse oblige from the five-star hotel to the three-star travellers.

June 20, 2013

Like working the Tokyo subway at rush hour, I push essentials into the carry-on, determined to make do for six weeks: By the sea (Dalmatian coast) at the galleries (Venice Biennale) in the glaciers (Switzerland) among the wine-soaked (Bordeaux) and with the chic (Paris).

Parisians do it with scarves. But they’ve got Hermès‘ guide, 16 full-colour pages of scarf-tying lessons. No time to borrow one. Got to get to the airport.