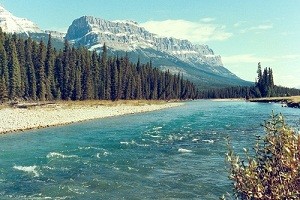

When returning from Rome on an Alitalia flight, some people were sleeping and others watching the movie when we hit a major area of turbulence. Cups and glasses went flying and gave new meaning to the often ignored advice of ‘buckle up for safety, at all times’. Once my stomach had returned to the confines of my body, I opened the window blinds and looked out on a spectacular icescape. Sparkling white glaciers and milky blue-green lakes tumbled off high cliff edges into an ebony sea and were in stunning contrast with a bright blue sky. There wasn’t a cloud in sight and besides wondering whether I was looking down at Iceland or Greenland, I couldn’t help but be puzzled as to what had caused the turbulence.

When returning from Rome on an Alitalia flight, some people were sleeping and others watching the movie when we hit a major area of turbulence. Cups and glasses went flying and gave new meaning to the often ignored advice of ‘buckle up for safety, at all times’. Once my stomach had returned to the confines of my body, I opened the window blinds and looked out on a spectacular icescape. Sparkling white glaciers and milky blue-green lakes tumbled off high cliff edges into an ebony sea and were in stunning contrast with a bright blue sky. There wasn’t a cloud in sight and besides wondering whether I was looking down at Iceland or Greenland, I couldn’t help but be puzzled as to what had caused the turbulence.

In the last few years I have encountered various forms of turbulence.  There’s the tortuous bumpy type which usually occurs when the plane is skimming across the surface of the clouds. Stomach-churning turbulence has had me bouncing around in the ominous grey and black clouds of thunderstorms with their violent up and down drafts, heavy rain and hail content. Then there have been the momentary heart-stoppers caused by changes in air temperature— a hot, violent and destructive chinook blowing over Calgary, for example— or if the plane is flying in a northerly or southerly direction and has to cross the jet stream, a river of air that encircles the earth and contains winds that move up to 500 km per hour.

There’s the tortuous bumpy type which usually occurs when the plane is skimming across the surface of the clouds. Stomach-churning turbulence has had me bouncing around in the ominous grey and black clouds of thunderstorms with their violent up and down drafts, heavy rain and hail content. Then there have been the momentary heart-stoppers caused by changes in air temperature— a hot, violent and destructive chinook blowing over Calgary, for example— or if the plane is flying in a northerly or southerly direction and has to cross the jet stream, a river of air that encircles the earth and contains winds that move up to 500 km per hour.

Fortunately I have never experienced Clear Air Turbulence which cannot be anticipated by the pilot. When the plane enters this field it can unexpectedly drop altitude causing chaos in the cabin and injury to people who were walking about at the time. Pilots immediately report this rare phenomenon to Air Traffic Control and give details of time, location, flight level and intensity so that the information may be passed on to other flights in the area.

With all our modern technology, you would think that turbulence, for the most part, could be avoided. And it can, but there are other factors that play a major part.

Think of the sky as an ocean

One pilot explained the sky to me in simple terms. “Think of it as an ocean” he said “With all the currents and tides, calm and choppy waters, heavy swells and powerful wave action. We receive maps each morning that tell us the different fronts and weather conditions we are likely to encounter and our route is generally designed with those in mind. If we spot a certain cloud formation and know we are due for a bumpy ride we can request a change of altitude from Air Traffic Control. There might be other planes in the area at different flight levels and flying at faster or slower speeds, so ATC may take several minutes to get back to us while they consider the safety implications of giving us a smooth ride. By that time we may be through the turbulence.”

One pilot explained the sky to me in simple terms. “Think of it as an ocean” he said “With all the currents and tides, calm and choppy waters, heavy swells and powerful wave action. We receive maps each morning that tell us the different fronts and weather conditions we are likely to encounter and our route is generally designed with those in mind. If we spot a certain cloud formation and know we are due for a bumpy ride we can request a change of altitude from Air Traffic Control. There might be other planes in the area at different flight levels and flying at faster or slower speeds, so ATC may take several minutes to get back to us while they consider the safety implications of giving us a smooth ride. By that time we may be through the turbulence.”

Besides safety, another key factor is money. The costs of running an airline are high and fuel is at a premium. With competition and airlines offering similar time schedules to attract peak business, companies vie to get their planes off the ground and in the air as fast as possible in order to get the optimum position. To do it, the ground crew has to work quickly and efficiently on everything from maintenance, fueling, cargo and baggage handling, food service, and boarding the passengers.

Flying high saves fuel

When the aircraft takes off it is heavy with cargo, passengers and fuel. Its goal is to reach altitude as quickly as possible since it burns less fuel once it is level. As the journey continues and fuel is burned, the weight of the plane becomes lighter and, if authorized, can be moved up to a higher altitude. The higher you fly, the thinner the air, the less resistance on the plane and the more fuel can be saved. And fuel costs money.  Put another way, if the airline can save 6 minutes on an 8-hour flight then depending on the equipment they could be saving up to 4,000 kg of fuel. If the company has 300 planes in the air each day and can save 4-6 minutes on every flight, then at today’s prices that translates to significant savings.

Put another way, if the airline can save 6 minutes on an 8-hour flight then depending on the equipment they could be saving up to 4,000 kg of fuel. If the company has 300 planes in the air each day and can save 4-6 minutes on every flight, then at today’s prices that translates to significant savings.

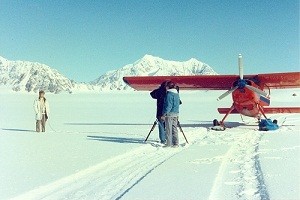

The majority of passengers today, however, want cost-effective travel and a stress-free flight. On that memorable day returning from Italy, Senior Alitalia Captain, Stefano Di Giovanni recommended that nervous travellers stick to the larger and heavier planes that tend to be more stable in turbulent conditions. As for his flight plan? He had been given all the information about the route, there were no planes ahead to warn of turbulence and no phenomenon forecast over Greenland. And those few seconds that had seemed like an eternity as our plane was plunged into a dance with the sky, he explained, were due to the sun reflecting warm air off the enormous 15,000 foot high ice plateau.